The film-makers who shot the seminal 60s documentary on alcoholics and vagrants, How Do You Like The Bowery?, have exclusively revealed how it was originally panned – before being hailed as a classic.

In their first ever interview about the film, Alan Raymond and Dan Halas have told how they were students at NYU when they wandered over to the infamous Lower East Side avenue to ask its residents just one question: “How do you like the Bowery?”

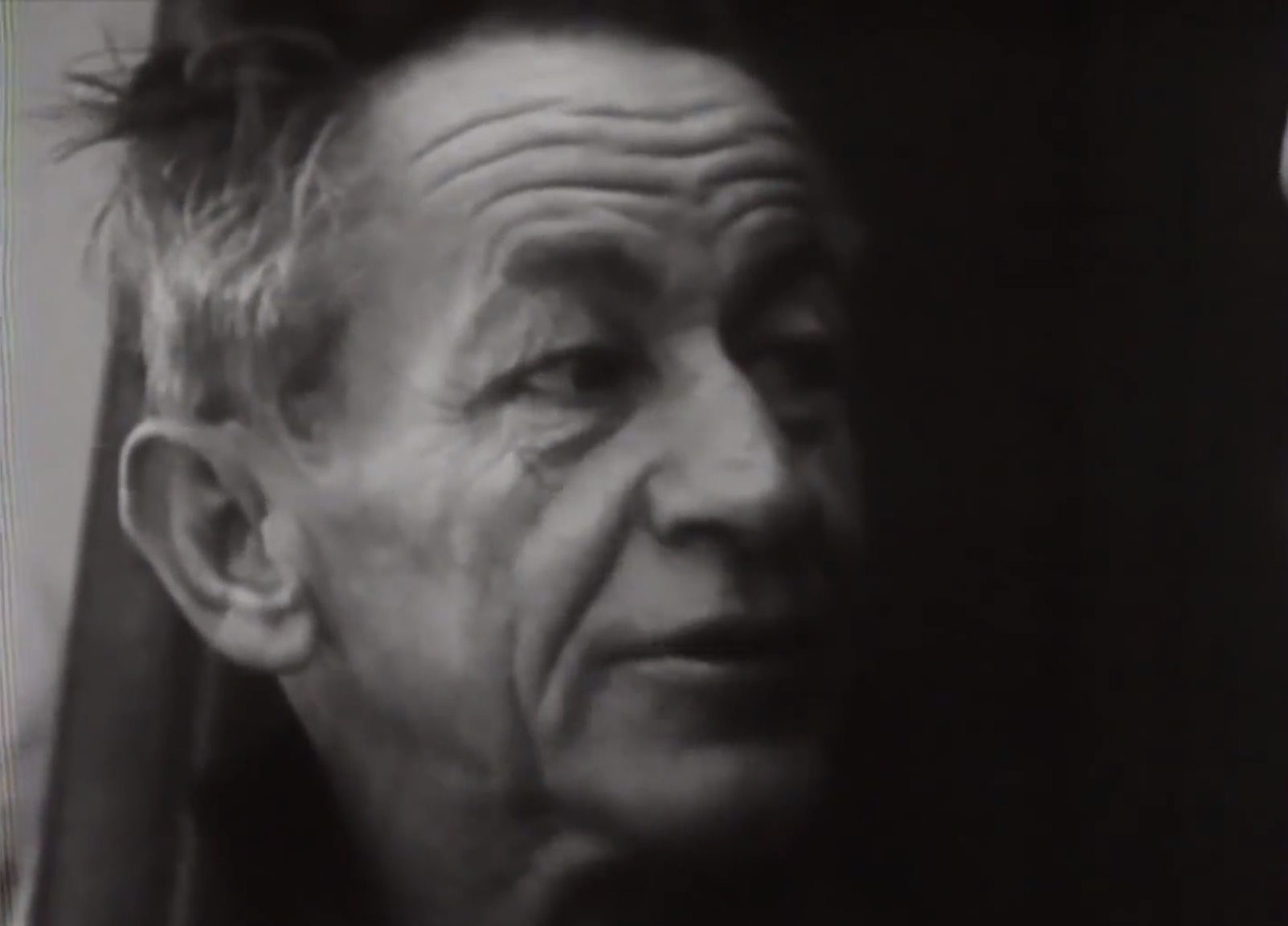

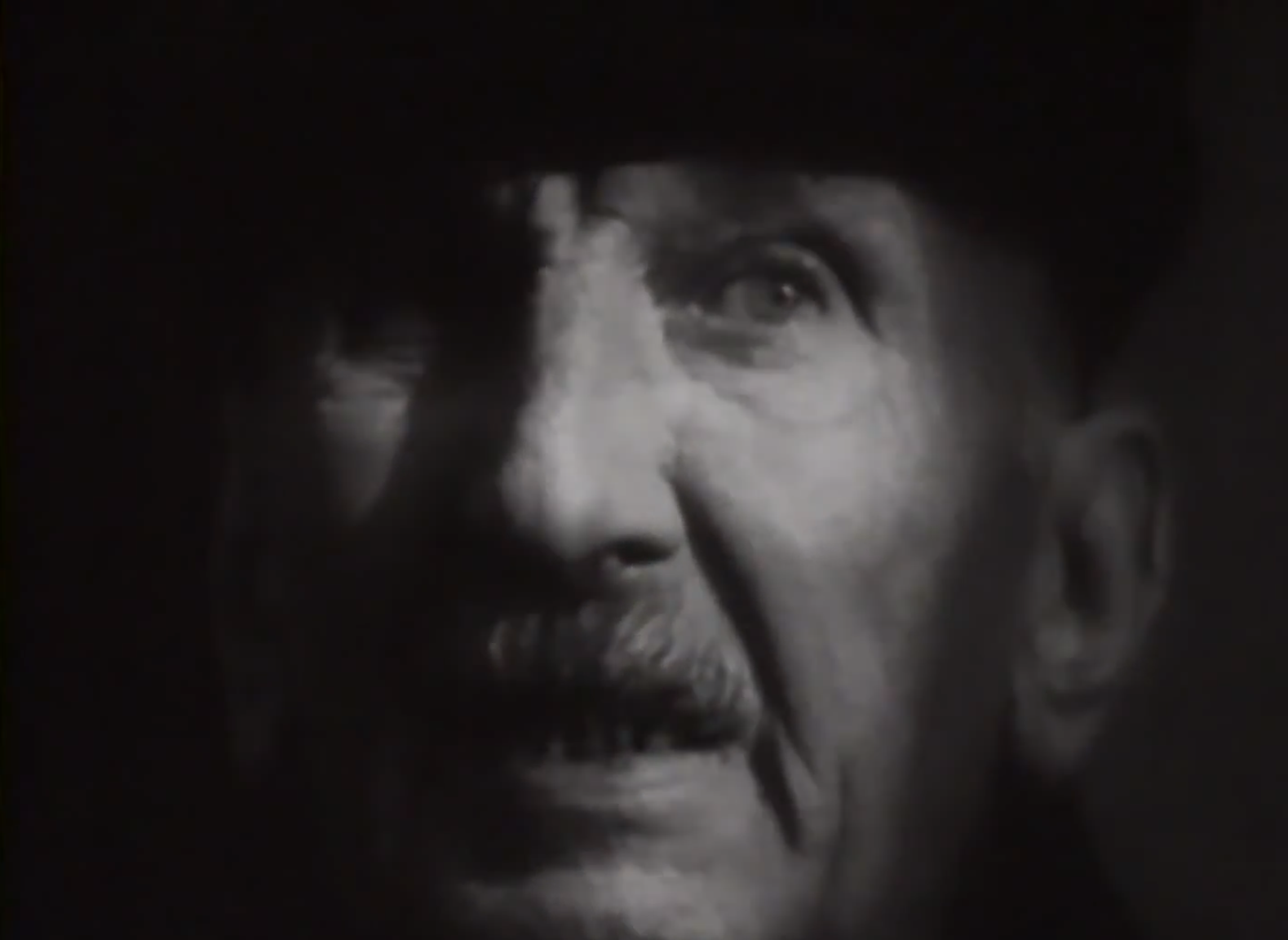

The men’s responses – which are shot in stark close-up, showing every facial crease and missing tooth – range from the optimistic to the downright tragic.

One man, whose swollen nose makes him look like WC Fields, says: “I’ve been in the Bowery 14 years. I was working nine years in a place and my wife got killed by a car and that’s why I’m down here. I don’t really like it, but misery likes company.”

Another down-and-out with haunted eyes stutters: “I come here on the Bowery for one reason – only one reason – I, I, I, I killed my wife. I loved her very dearly. I backed out of the garage with my car in Cincinatta. I didn’t know she was behind me – I just want to go with her. I wanna go with her…forgive me, forgive me.”

A woman clad only in a coat lies on her back on the sidewalk as snow snakes down the Bowery, uncrossing and crossing her legs, naked white thighs exposed to the bitter cold.

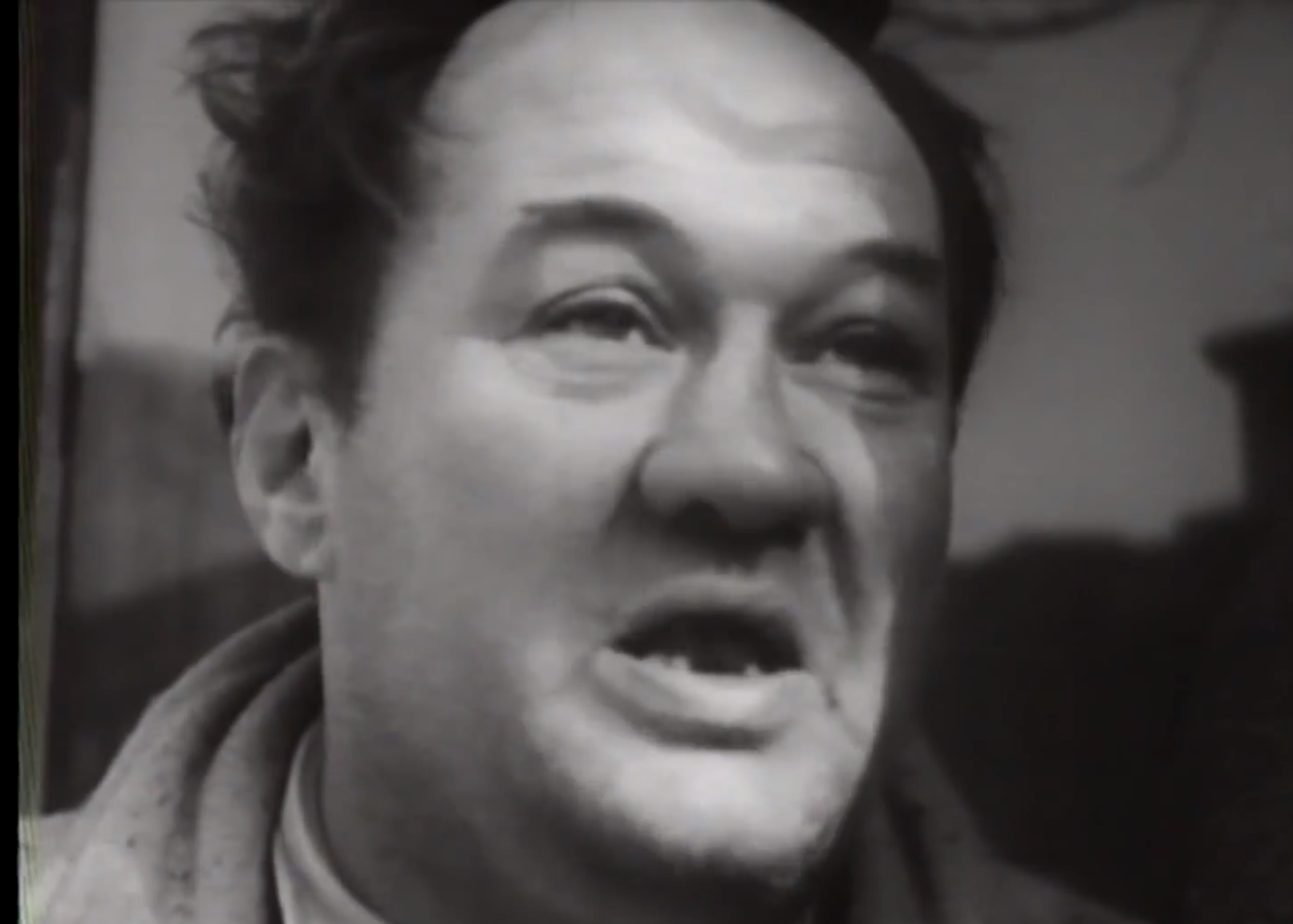

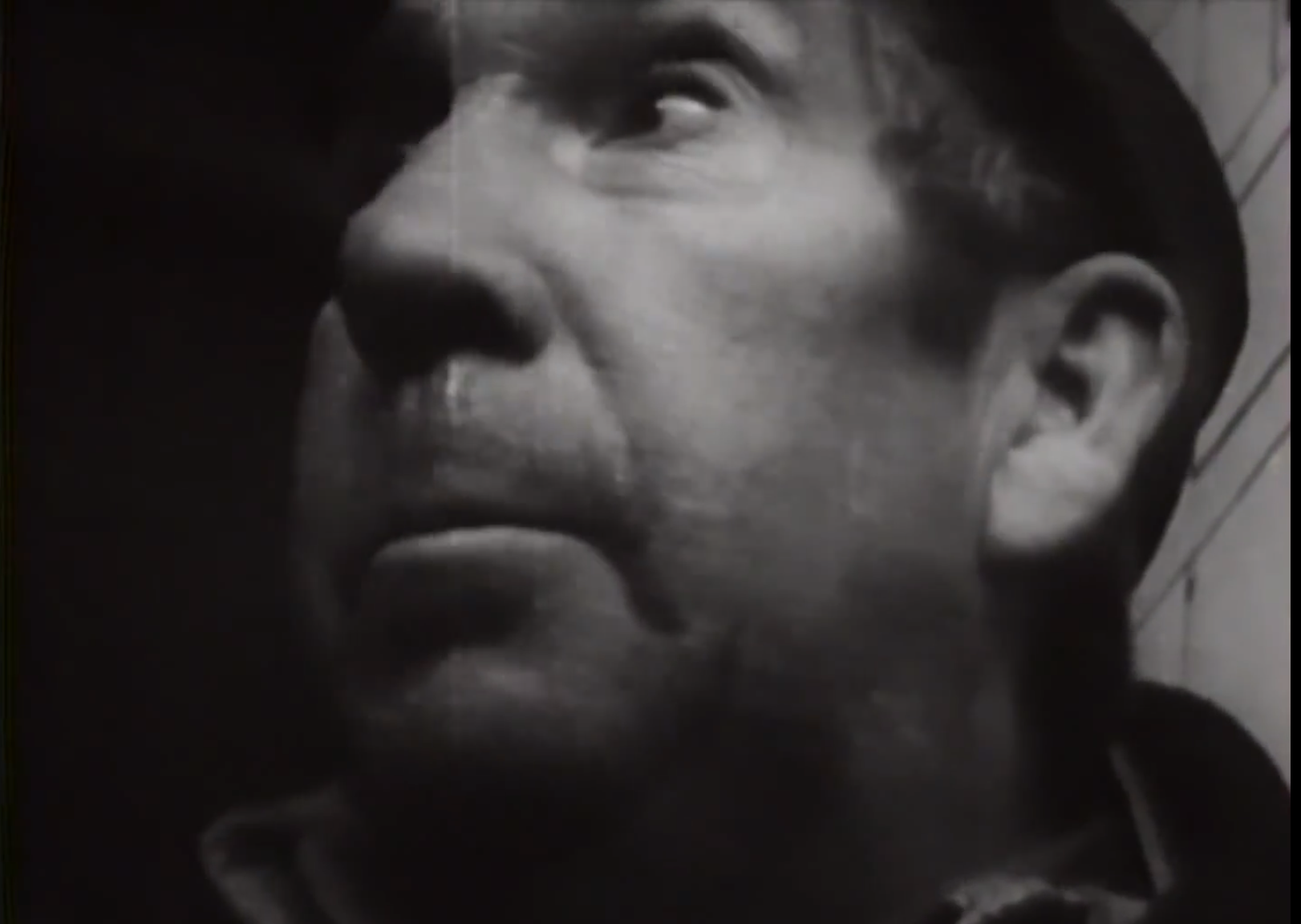

But if there can be a star of the film, it is an explosive, almost cartoon-like character called West Side Red, who talks about himself in the third person and seems like he could have walked off the set of On The Waterfront.

Looking like a beat-up Jimmy Cagney, he says: “West Side Red was over on Pier 90 – the pistol local 824. Red is a retired gunman, but I don’t work no more so they leave me alone because I retired. I retired about four years back. Red retired ‘cause I did a bit in Sing Sing and that cured me, I don’t wanna go back to jail no more, you know?”

The 12-minute film was made in 1961 as part of an advanced production class in the undergraduate program at Washington Square College.

“We shot the film over a number of weekends and I think right away we knew we were on to something. The footage of the men was just so raw and compelling with one great story after another,” says Alan, who has won an Oscar and countless Emmys for his film work. “We were aware that we were dealing with emotionally damaged people and that was a heavy burden for us.

“But that’s a cross that all serious social-issue documentary filmmakers have to bear. If you’re going to penetrate a sub-culture, especially one in which your subjects are poverty stricken or otherwise disadvantaged, then you’re going to be emotionally burdened by that to a degree. You just accept it and try to remain dispassionate during the filming.

“Unlike today, the Bowery then was a genuine ‘skid row’ with more than 25 flop houses and men suffering from severe alcoholism. It was light years away from the gentrified part of Manhattan it is today. Most New Yorkers at the time avoided it and considered the men there to be ‘bums’.”

Dan, who was 25 when they shot the film, says: “The Bowery was near NYU and we thought it was a colorful area that would lend itself well to a school project. We were too involved in making a film rather than being afraid of our subject matter. We were there for a purpose, not to proselytize or judge.

“I thought the tight shot to be most effective and wanted to make a film as good and as lasting as Un Chien Andalou.”

Dan took six months to edit the film in his Bronx apartment, saying: “We barely had enough footage to make one film – I used everything! I cut the staircase sequence first and knew how I wanted to start and end it, and that I wanted the woman in the snow about the middle or coming to the end. I struggled for months until I came up with the correct montage.

“From my exposure to literature in my childhood and young adulthood, I knew what a story was. Even though Alan and I were making documentaries, I knew there needed to be a sense of storytelling in film – without that, this would just be another social documentary.”

But while the pair felt they’d created something unique by capturing the voices of these desperate, broken men, the people that they’d hoped to impress with the film thought it was terrible.

Alan – who was just 20 at the time – explains: “When we screened the silent rushes, we were roundly criticized by both our fellow students and the professor running the class. I would say they actively disliked it. They just thought we were too crude in our film making abilities and kind of wrote us off as outlaws and eccentrics.

“Dan was a year ahead of me, a senior, and he received a grade of D for the course. Because I was just a junior I think the professor was a bit kinder to me. I got a C for my course grade.

“All of this was quite depressing and I recall being pretty disappointed after all our hard work. Dan had really worked very hard on the editing, then to be given a D. Yikes. But then a wonderful turn of events happened.

“The film critic Stanley Kauffman, who wrote for the New Republic, had a local television show called The Art of Film. He called NYU and said he wanted to devote one of his programs to student film making, which was then in its infancy.

“And wouldn’t you know, he picked our film to show. So How Do You Like The Bowery? actually aired on the New York City PBS station. And Stanley Kauffman was effusive in his praise, saying we had done a great job of capturing the reality of the “lost souls” on the Bowery.

“The experience of being first criticized and then praised for the same film was a great life lesson for me. I came to realize that not every film you make is understood or appreciated at the time you make it. And, in fact, How Do You Like The Bowery? is a true document of a bygone era in New York City and has both historical and sociological importance.”

Both Alan and Dan say that many of the interviewees have remained stuck in their minds, though neither of them kept in touch with the men or followed up on their stories, as they thought the film would only be shown within an academic environment.

Alan says: “I guess my favorite interview was with West Side Red. When he refers to himself in the third person ‘Red is a retired gunman’ it’s just so bizarre, and his beaten up and ravaged face is such an indelible image in my mind that I don’t think I’ll ever forget him.

“I do recall freezing up when that guy with the really deep voice said he hated the Bowery and then got kind of angry and said ominously ‘They don’t care’. It was a bit of moment for me to figure out how to keep him talking without going into some serious meltdown.”

Dan says: “We were not out there to make friends but to satisfy a student project, therefore I only see them on film as a constant reminder of their presence. As I edited the film, my goal was not to choose a favorite but form all their comments into a cohesive form.

“But I have to say my favorite was West Side Red. Even I was taken aback by him, despite being hardened by inexperience. They all affected me each in their own way.”

Alan added: “The question ‘How do you like the Bowery?’ was the perfect question to trigger the great responses we got. Obviously the question is somewhat ironic as we’re asking destitute and alcoholic men how they like the grim neighborhood they’re living in. But surprisingly the answers are all over the place, from saying it’s a great place to hang out, to saying it’s horrible.

“In some strange way, I think the men on the Bowery had it easier back then because it was an urban environment that in some way accommodated them with the flop houses, where they could sleep for very little money, to the camaraderie on the street where a bottle would get passed around, to the hands-off attitude of law enforcement, to the soup kitchens where they could get a hot meal.

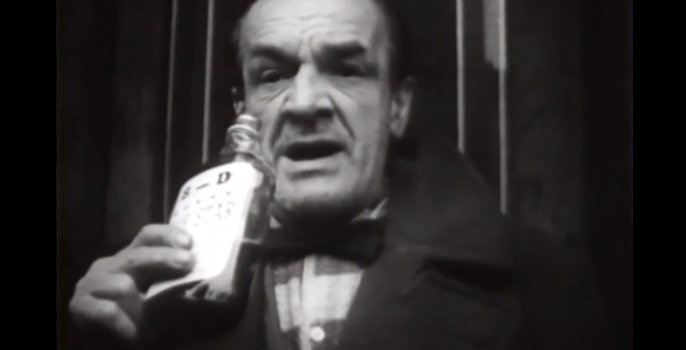

CANDID…the subjects were brutally honest about their circumstances. This man confesses ‘I’m an alcoholic’

“I’m not saying they had a great life. But they had a place for themselves, a place where they could disappear from society and lead a dissolute life that was tolerated by the people around them and by the city as well.

“None of that exists today. There’s no place for them to go. The Bowery is a highly gentrified neighborhood anchored by the New Museum, where our film was shown a year or two ago. All that’s there now are hotels charging $500 a night. It’s light years away from the era of the flop house.”

Though the film-makers didn’t keep in touch with any of the men, Alan admits that – in his subsequent professional career – he has always tried to stay in contact with his subjects, sometimes for years at a time.

When he shot the Loud family for the award-winning An American Family – considered the first ever reality TV show – he stayed friends with the Louds for over 30 years, and even went back to make another film with them, Lance Loud! A Death In An American Family.

Dan and Alan continued to work together for a number of years after they graduated from NYU, until Dan got drafted into the Army as a private. “I was drafted in 1966 and spent my entire time at the Army Journalism School in Indiana teaching lieutenants photography: still and motion picture,” he says.

“They drafted me not knowing I was bipolar but they rewarded me for serving my country. The Veterans Association facility here takes good care of me as a result of my being drafted.”

The pair made one last film together, One For Parole, about the last days in prison of a convicted murderer. Dan later gave up film-making to become a writer of fiction, and his work has appeared in publications such as Esquire and the prestigious Antioch Review. Currently, he’s working on a book titled Little Stories for Big People.

While Dan was in the Army, Alan met his wife and producing partner, Susan Raymond, and together they set up their company, Video Vérité, which focuses on documentaries.

Shortly after An American Family was broadcast in 1973, they produced The Police Tapes, about a high-crime police precinct in the South Bronx, that went on to win multiple awards, including three Emmys, and became the inspiration for Hill Street Blues.

In 1994, they received an Academy Award for their cinema vérité documentary on an inner-city elementary school called I Am A Promise: The Children of Stanton Elementary School.

Alan says: “Life takes many strange turns and since my entire career has been spent making long-form social-issue documentaries, I’d have to tip my hat to the men of the Bowery for making me understand the power of bringing real life stories to television.

“We’re just finishing an HBO Documentary Films original production on extreme sentencing called To Live And Die On Yard A. And we’re just starting a new American Masters film for PBS.”

As for How Do You Like The Bowery? Alan and Dan are still pleased with how it turned out.

“I’m always surprised that the film has remained so relevant and watchable,” says Alan. “Even though it is quite rough around the edges, I don’t think we could have done a much better job with the resources we had at the time.

“It might have been nice if we had more film to shoot, then we might have been able to make a slightly longer film. But the fact that it’s still being appreciated by audiences 50 years after it was made is amazing to me.”

“I’m satisfied with the film as it stands,” adds Dan. The only question I asked gave me more than enough reactions and responses. Everything in the film stays with me, especially the woman lying on the sidewalk in the snow: you can feel the cold.”

*Click here to watch How Do You Like The Bowery?

« Top 10 cheapest New York vintage stores Heat is on for Boardwalk Empire band »