The Chrysler Building, considered by many to be the most beautiful work of architecture ever constructed, is 85 years old today.

The Art Deco jewel was – at 1046ft – declared the tallest in the world on May 27, 1930.

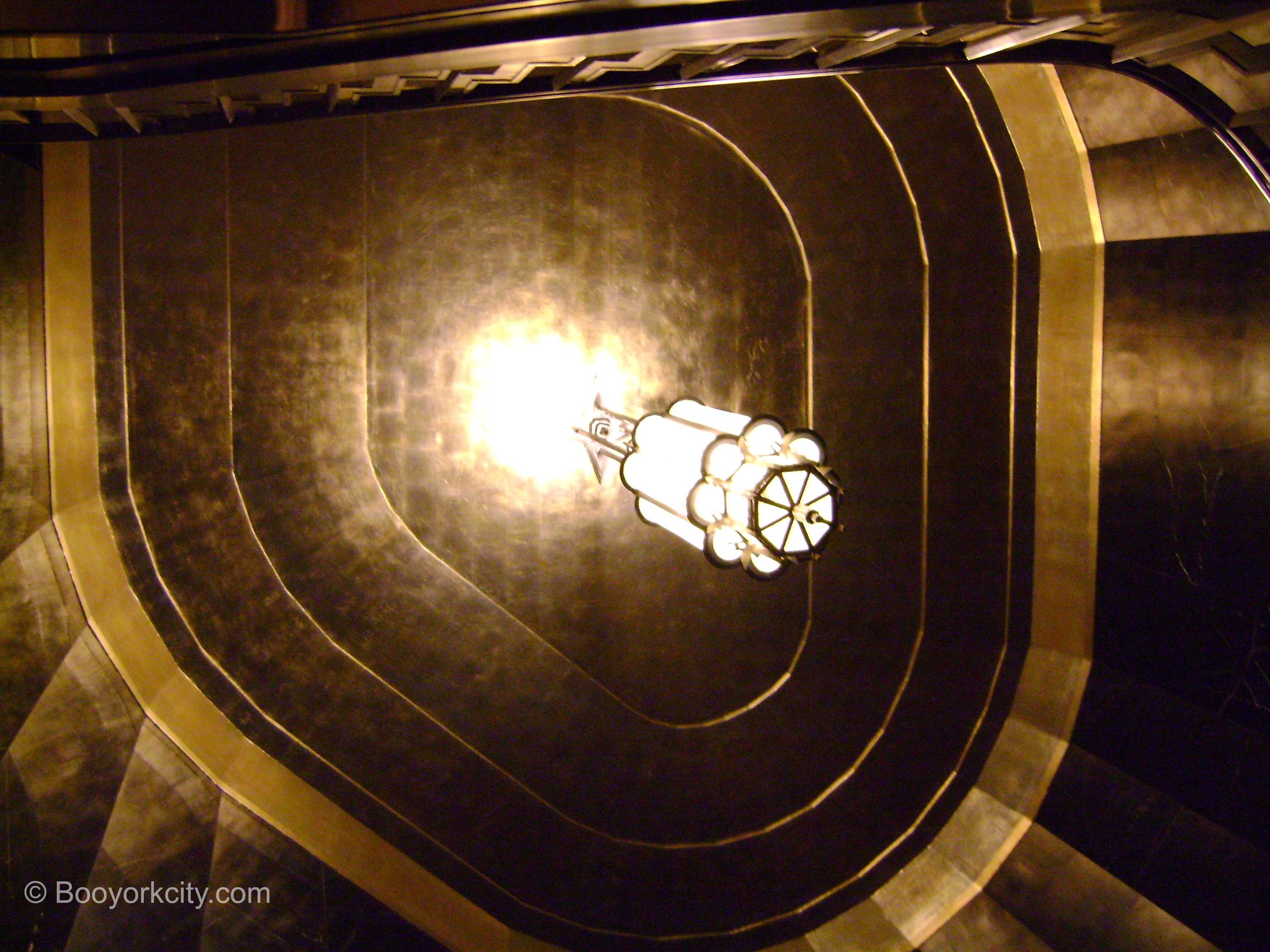

Its silver revolving doors capped with modernist zigzags and triangles lead into a spectacular lobby of polished rust-red African marble.

Above is Edward Turnbull’s Transport and Human Endeavor, the largest-ever painting at the time, which was created on canvas and cemented to the ceiling. Depicting airplanes, car assembly lines, and the construction of the Chrysler itself, it was a fitting umbrella to a lobby that was originally a car showroom.

Everything in architect William Van Alen’s masterpiece is designed to be a feast for the eyes – even the elevator doors show plant forms created from inlays of rare woods, and black-and-white striped marble floors in the shopping precinct in the basement.

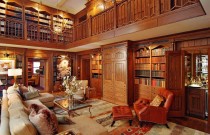

Perhaps its most spectacular secret was the now-defunct Cloud Club; a private members club, just below the Chrysler’s polished sunburst crown, on the 66th, 67th, and 68th floors. It opened in 1930 as a men-only lunch club, its room decorations an uneasy compromise between Van Alen’s modernist style and owner Walter Chrysler’s preference for faux baronial.

As well as dining rooms replete with murals, there was a barber’s shop, humidor, kitchens and a locker room, where booze was stashed during Prohibition.

Charles McGrath of The New York Times said the space seemed “almost preposterously small by today’s standards” and because of all of the facilities inside it, its ‘backstage’ areas “must have felt like a submarine – or, rather, like a very cramped airship”.

Henry Luce III, who visited the Cloud Club once with his father when he was 12 or 13, said: “I remember the wind whistling through very noisily. You could hear it inside.”

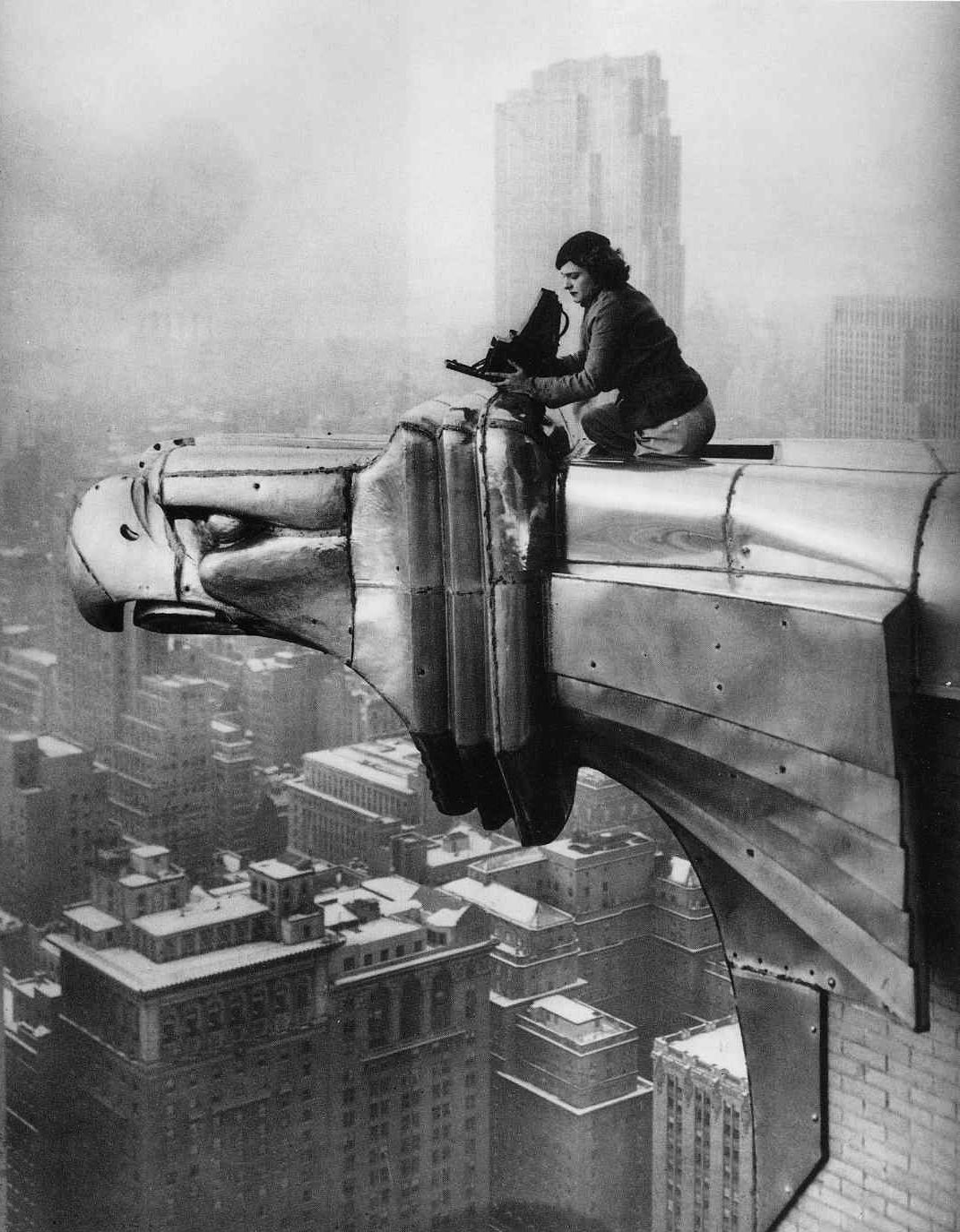

The Chrysler Building’s exterior is equally stunning, with white brickwork pattered with grey chevrons, stripes and wheel shapes. The imposing eagle heads and winged discs – famously captured by photographer Margaret Bourke-White, who had a studio in the Chrysler – are giant replicas of hood ornaments and radiator caps from 1929 Chrysler cars.

Van Alen originally designed the building with a glass crown, as well as a base with triple-height car showroom windows topped by 12 stories with glass-wrapped corners, to make it look like it was floating in mid-air.

However, as these ideas were so expensive, Van Alen redesigned it to make it taller, as during the 1920s, there was enormous competition to have the highest building.

When the Chrysler was near completion, a rival skyscraper at 40 Wall Street claimed to be the world’s tallest, so Van Alen got permission to build a 125ft long spire and had it secretly constructed inside the structure, stealing the title. But the Chrysler didn’t keep its record for long, as it was overtaken by the Empire State Building just 11 months later.

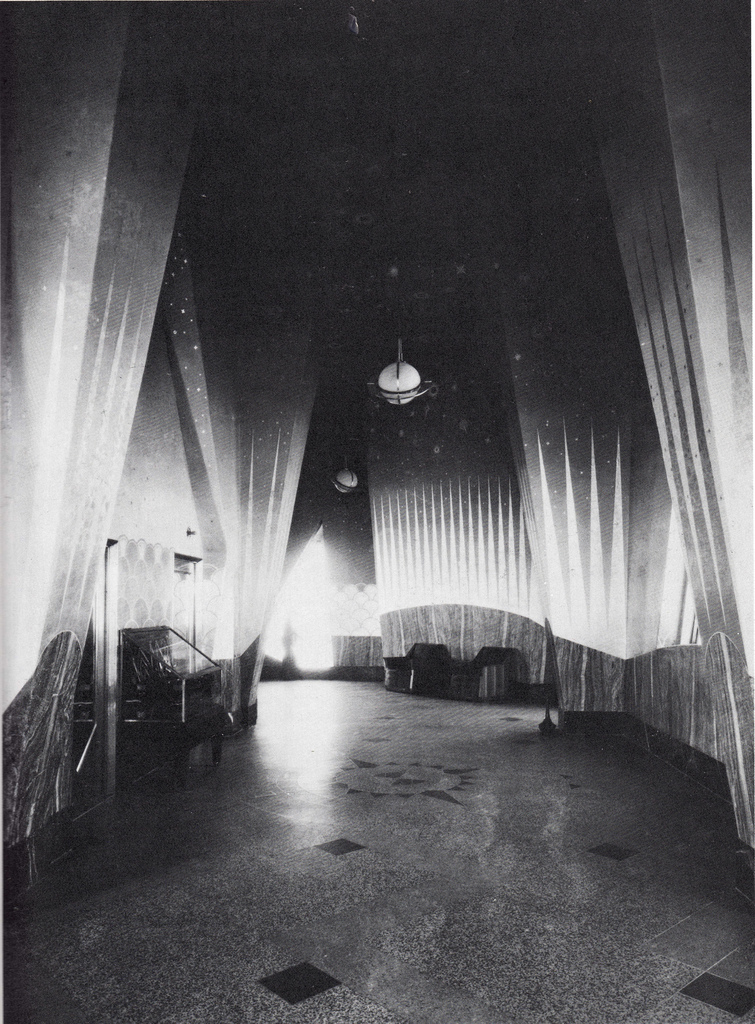

When the building first opened, it contained a public observation deck on the 71st floor, which had a celestial theme, with sunbursts splashed against the walls and Saturn-shaped light fixtures, but this was closed to the public in 1945.

The Cloud Club itself closed in 1979 and fell into disrepair, with water and rot destroying its murals. Property management company Tishman Speyer took over the Chrysler in 1998 and refurbished the club to lease to tenants, removing most of the evidence of its glamorous former life.

Though the Chrysler Building was Van Alen’s greatest architectural achievement, he had little to celebrate when it was completed.

He requested payment of six per cent of the building’s $14million construction budget – a standard fee at the time – but because he had failed to sign a contract when he received the commission, Walter Chrysler refused to pay the balance of his fee.

Van Alen sued him and won, eventually receiving the fee after years of legal wrangling. However, his reputation as an employable architect was compromised by the lawsuit and his career was effectively ruined.

And in a bizarre twist, Van Alen’s optimistic symbol of the hedonistic Jazz Age – a time of guzzling gin, flappers dancing the Charleston, and the burgeoning liberation of women – is 90 per cent owned by Abu Dhabi Investment Council in the UAE; an Arabic country that forbids the drinking of alcohol and where women are frequently flogged or stoned to death for sex outside marriage or adultery.

« Hands up for a feminist manicure Rich and famous flock to Hotel des Artistes »