You know the scene: a cyclist is in front of your car and you feel they’re going far too slowly for your busy life. You shout “Get off the road!” as they pedal ahead, deaf to your fury.

There’s just one problem – it’s not your road. Never was. It was cyclists that built the roads in New York City.

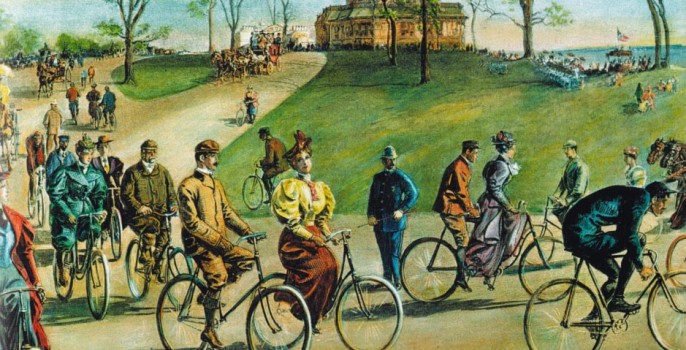

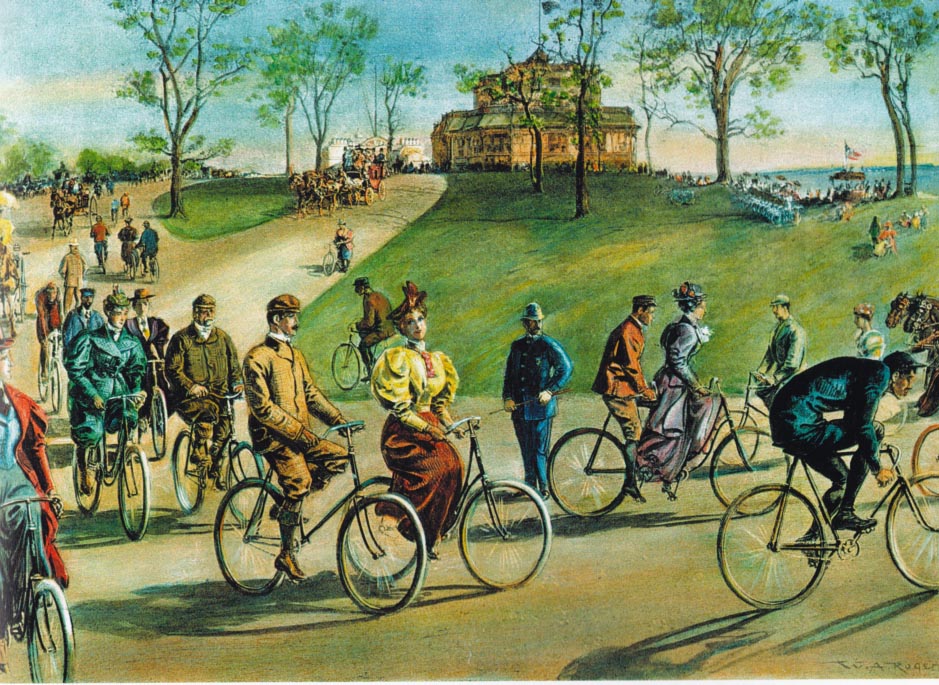

In the 1890s, years before petrol-driven cars appeared, there was a boom in cycling, led mainly by the richest people in society adopting it as a fashion. They campaigned ceaselessly – and stumped up some of the money themselves – to have the rutted roads re-laid as flat as billiard tables, so they could enjoy their pastime more fully.

Brooklyn mayor Frederick W. Wurster even said in 1896: “The bicycle I look upon, to a large extent, as the pioneer of good roads. The bicycle has done more for good roads, and will do more for good roads in the future, than any other form of vehicle.”

Author Carlton Reid, who has written the new book, Roads Were Not Built For Cars, said: “Rural roads – in areas which are now urban – obviously existed before cyclists but had largely gone out of use from the 1840s, due to the railways. Cyclists brought these roads back into use and clamored for their improvement – even the organization that would become the Federal Highway Administration was largely set up thanks to lobbying by cyclists.”

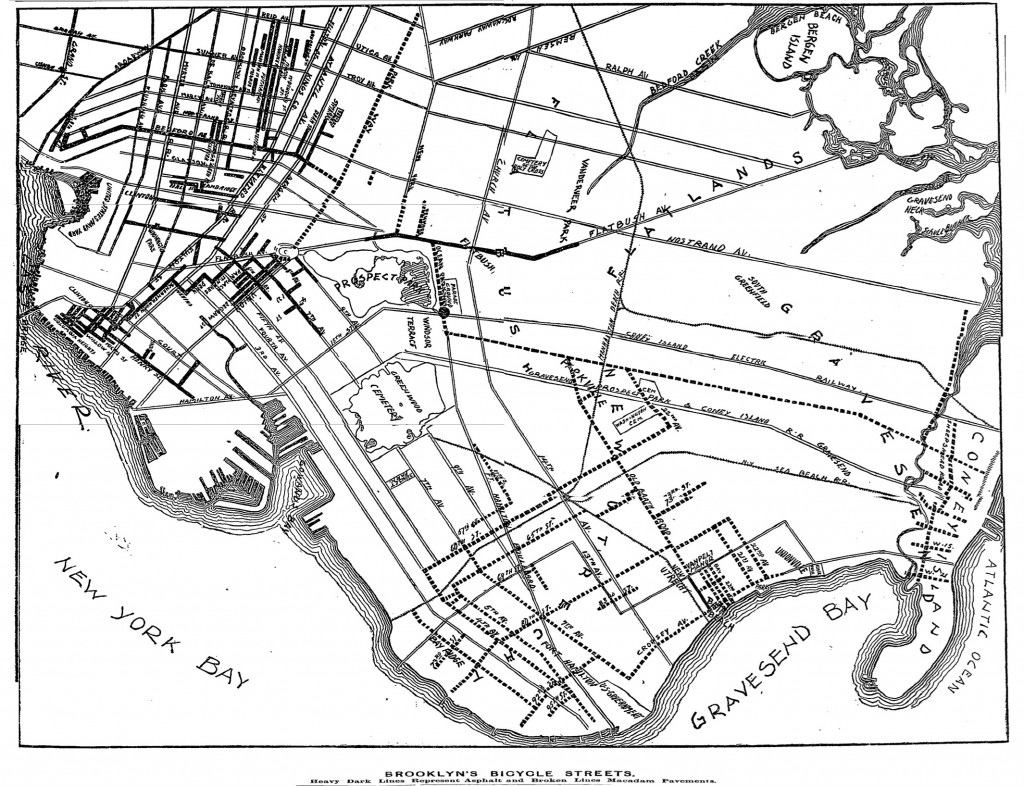

By 1895, there were 20 miles of asphalted roads in NYC partly created for the comfort of cyclists, who were pedaling around in corsets and stiff collars. The New York Times even printed a map showing “the streets that are best adapted for good wheeling” with roads radiating outwards from downtown to what were then open fields.

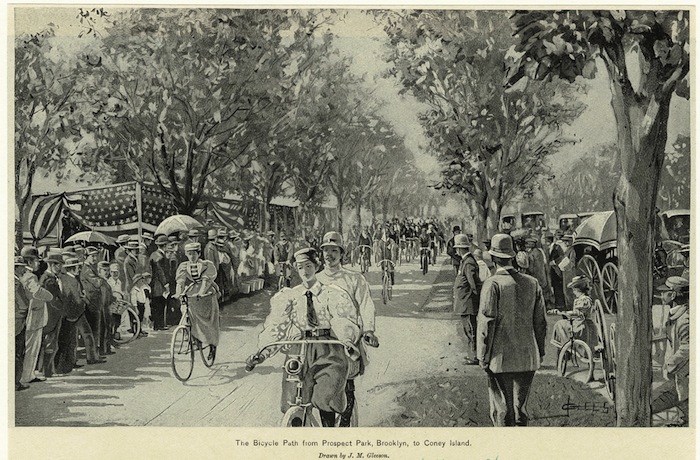

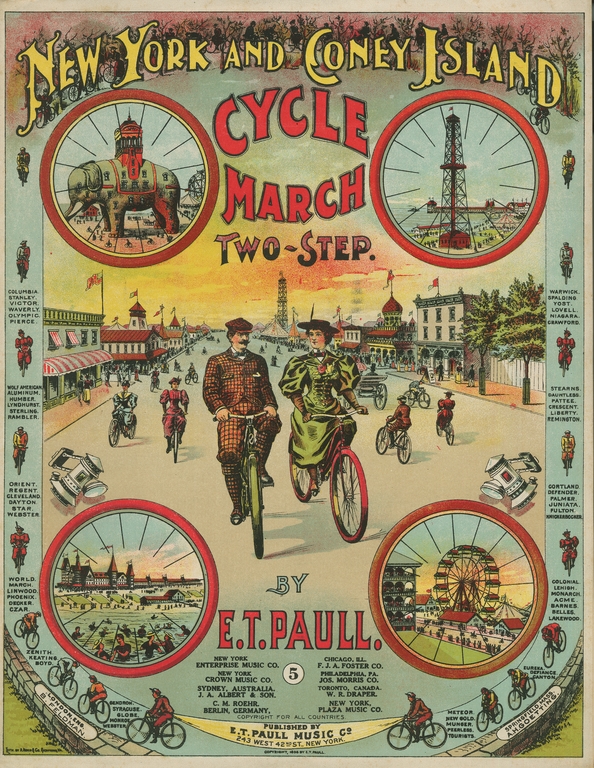

New York also had one of the first bike paths in the world, and it was certainly the best. Built in 1894, the Coney Island Cycle Path extended for five-and-a-half miles from Prospect Park in Brooklyn to the beach resort.

It was an instant success, with thousands using it on its opening weekend. And when a return path was built on the opposite side of the boulevard two years later, 10,000 cyclists attended a gala parade, watched by 100,000 spectators.

A great many cycling clubs – frequented by the filthy rich – partly paid for the Coney path to be built. The League of American Wheelmen’s Good Roads Association on its own paid $3,500 of the $50,000 needed.

Cycling was also hip – in Brooklyn alone, there were 80,000 cyclists in the 1890s. With these huge numbers, and the support of high society, creating bicycle infrastructure in places such as Pelham Parkway, and Riverside Park and Drive, was as easy as cycling along the new roads themselves.

Reid explains: “Many American roads were segregated, especially the new resurfaced boulevards. High-class carriages and bicycles could use these posh roads, but lumbering wagons couldn’t.”

There was also another kind of segregation in operation; that between rich and poor. Bicycles and tricycles were expensive machines, making cycling a high-society and middle-class pursuit.

The wealthiest socialites, such as the Astors, Rockefellers and the Roosevelts, were members of New York’s most exclusive cycling club, the Michaux, which was founded in 1894.

The New York Times described one charity meeting of the club in 1895: “The old Claremont mansion, gayly bedecked with bunting for the occasion, was filled with a fashionable throng. There were groups of beautifully gowned women and well-groomed men on the piazzas and out on the green lawn. Every other moment, a small squad of correctly dressed bicyclists would alight and turn their wheels over to the servants.”

But though cyclists pioneered the push for good roads, it was the car that benefitted the most from them, just as it did with the transfer of cycling’s technological advances, such as lightweight steel tubing, pneumatic tires, ball bearings and differential gears.

By 1897, sales of new cycles reached a peak and a steady decline set in. High society took to motorcars; the rest migrated to trams. Though one upside to cycling’s fall in popularity amongst the rich was that it suddenly became affordable to the working class, in part due to the glut of second-hand bikes on the market.

But by 1900, the Coney Island Cycle Path had fallen into disrepair and in 1911 – with the city fathers fully in thrall to the car – 3,000 cyclists rode along it “to arouse a public sentiment against the closing of the cycle path on the Ocean Parkway”.

The path still exists today, though in a much reduced form. The return path became a road and the Ocean Parkway is now a multi-lane highway, with a slim bike path and a separate walking path. Both paths have to cross over many roads, with priority now granted to cars.

Today, NYC may not have as many traffic-free boulevards and rural beauty spots to enjoy as cycling’s new-road pioneers, but the 100,000 subscribers of the massively successful Citi Bike scheme perhaps point to a renaissance of cycling in the city.

Reid himself has a pragmatic take on the glory days of the Gay ‘90s as compared to the 21st century: “There was a lot that was objectionable about those times, such as the casual racism and horse shit on the streets. Also, cycling in cities, despite a lack of motorcars, wasn’t totally safe. Carriages drawn by large teams of horses were a danger to cyclists and the roads were chaotic.

“But there was also lots to admire – the sophisticated clothing, the music, the lack of speeding motor cars. And, out in the boondocks, the bicycling must have been idyllic.”

One Response

Leave a Reply

« A shot in the dark for Weegee Tribute to Van Alen with Chrysler hat »

[…] Turns out it was more than just rural roads that were paved first by cyclists. Cyclists in corsets built NYC’s roads […]